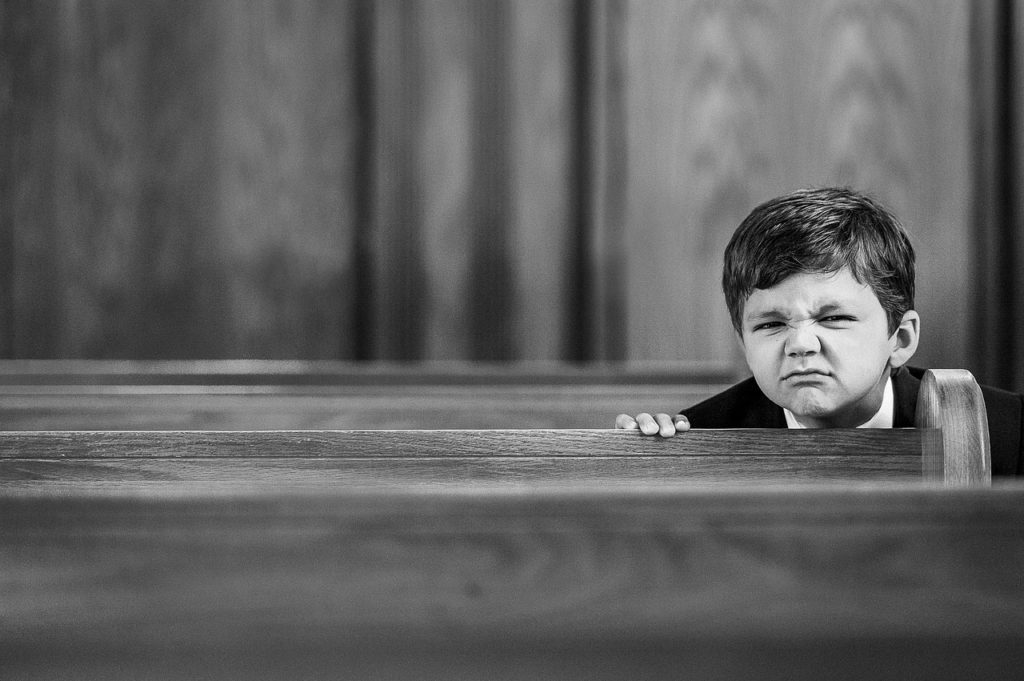

When I was a kid, Sunday church services were interminable. I thought that it might be a lot easier to endure if I had some idea as to where we were in the service. So I asked my dad, the pastor, if he could write out the service elements, in order, onto a piece of paper so that I could track along. I reasoned that the long bits, like the congregational prayer and sermon, might be easier to suffer if I knew where we were in relation to the end.

Being the child of the pastor, I thought I had privileged access to this information. He chuckled and showed me last week’s bulletin. There it was–The Order of Worship–a list of all the elements in the worship service. It had been there all along, for just anyone to follow. So every Sunday, I followed along and found that the church became less arduous when I knew where we were.

I discovered something else–every service followed the same pattern. The order of worship wasn’t this week’s order. It was every week’s order. Eventually, I didn’t need to look at the bulletin. I always knew where we were and the pattern became a comfort.

The Pattern of Worship

For a long, long time, all Christian church services were liturgical. They followed a regular and predictable pattern. Even after the huge disruption of the Reformation, services were still governed by a liturgy regardless of denomination.

I am only speaking from my own experience, but I began noticing some congregations were abandoning formal liturgies in the late 80s. I started seeing church signs announcing “Liturgical Services” at a different time from the “Regular Service.” Now we have lots of these modern, non-liturgical churches.

These have a very simple order of worship. If they did publish one, it would look something like this.

Songs

Sermon

Songs

I’m being a little facetious because there are a few prayers and an offering, but these events have been shortened and are now rather streamline. It should be noted that the songs will sometimes connect to elements of the old liturgy they’ve supplanted–songs of praise certainly, sometimes confession or Thanksgiving or even a re-worked apostles’ creed–but when we rely on songs to carry these liturgical elements, they are no longer weekly occurrences and this is significant.

I suppose we’ve simplified things so as to avoid confusing visitors to our Sunday service. After all, many of our neighbors are no longer familiar with church. This may be reason enough to keep the Order of Worship simple.

But perhaps we’ve lost something. Through the liturgies we practiced and learned together important patterns that are meant to shape the way we live out lives.

An Active God

What does God do during the church service?

In the modern, non-liturgical churches it is easy to get the idea that God doesn’t do very much. At least little is implied about his actions. During the songs, he might be sitting there listening and smiling. And what does God do during the sermon? He is of course speaking, but do we frame the sermon in such a way as to leave the congregants no doubt that it is not just the preacher who is speaking? Are the faithful are allowed to think God is listening indifferently–after all, he knows it all already. How many people would say that His attention is drawn to another church somewhere else in the world that happens to be singing at the time because God likes the singing part the best?

In modern, non-liturgical churches, it’s easy to think that the people are the main or only actors in the Sunday service. We arrive, we sing, we pray, we listen, we eat and drink and then we leave. (There is another scenario, which is a concern for worship leaders, were only the worship band is active, and the rest passively consume, but this is a topic for another day.)

God merely receives human worship.

Passivity is not a characteristic of God as presented in the Bible. The passivity we attribute to him is a product of secularization. In the West, we have created artificial categories between physical things and spiritual things and then we marginalize the spiritual things. The Western church is not immune to secularism. Lot’s of people still believe that God is there, but they aren’t really sure what he does. It seems like he’s a long way off, no doubt hearing our prayers, but is he really acting on them? Christians influenced by Modernism experience a narrowing and weakening the presence and power of transcendent things in the immanent frame.

By stepping away from traditional liturgies, we’ve not eliminated liturgies, we’ve just adopted new ones. If we haven’t been deliberate, we’ve simply replaced tratitional liturgies with secular ones. Thus promoting and perpetuating secular ideas through corporate worship.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”Some churches are promoting secular ideas through corporate worship because they’ve replaced traditional liturgies with secular ones. In secularized Christian worship, God is passive. Agency lies primarily with people. #worship #liturgy ” quote=”Some churches are promoting secular ideas through corporate worship because they’ve replaced traditional liturgies with secular ones. In secularized Christian worship, God is passive. Agency lies primarily with people.”]

Habits and Rituals

Habits, rituals, and liturgies are important. They shape how we think and they shape who we are. We can ritualize God’s passivity and the weekly repetition will eventually shape how we think, and even who we are. God’s passivity won’t just stay in church, we will eventually come to think of God as passive in our lives and in the world as well.

The converse is also true. If we shape our worship service around God’s active interaction with his people, this idea will leak into Monday and beyond.

Traditional liturgies shape worship as an active dialogue between God and his people–(all his people, not just the ones with instruments.)

The Call to Worship and God’s Greeting

The first words the worshipers hear in the service are important. At one service, the first words I heard were,

“I want to thank you all for coming to church this morning.”

Seriously?

Who greets us? This greeting is all about the actions of the worshipers. We have decided to come to church this morning. Apparently with some inconvenience, for we have earned gratitude from somewhere. Who owes us this gratitude? The worship leader? God? Does God owe us something because we chose to come to church instead of watching the first half of the football game?

The Call to Worship suggests that someone is calling. It is God himself who draws us to church. He gets the first word. We are not there because we chose to be there; we are not there because our parents made us come; we are not there because we are trying to impress that cute girl with our religious zeal; we are not there because this is what we always do on Sundays. We are there because God has drawn us there.

Our bodies are there, but where are our hearts and minds? The call to worship marks a turning toward worship, toward the throne of heaven, toward God. The preceding week was full of joys and challenges involving relationships, obligations, worries, and diversions. In the call to worship we are turned from ourselves, toward God.

And The Greeting is his.

What kind of people do we become if we are regularly thanked for deciding to come to church? What kind of people do we become if we repeat, week after week, God’s active calling to corporate worship?

Acts of Praise

Next comes an act of praise. Our action follows God’s action.

Importantly, this act of praise is not the result of the worship leader asking us to stand and sing nor is it caused by the first cords of music. Praise is the result of our attention being directed toward God.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”Praise is not the result of the worship leader asking us to stand and sing. Praise is the result of our attention being directed toward God. #Worship #PraiseandWorship” quote=”Praise is not the result of the worship leader asking us to stand and sing. Praise is the result of our attention being directed toward God.”]

This may not be automatic for everyone. But it’s what the liturgy teaches through repetition. With ritual repetition, this will eventually come to be our natural response.

To make the Sunday worship service just a bunch of human activity, well, that’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit without Roger Rabbit. Our Sunday worship needs to show God’s activity because he is active. If we can’t see what he does in Church, how can we see him as active in our lives, let alone the world?

God doesn’t just sit up in heaven waiting for Sunday when some people will sing songs at him. A weekly reminder that God calls us to worship will begin to change how we view ourselves, the world and the God who sustains it all.

Other posts in this series:

The Order of Worship (2): Confession

The Order of Worship (3): The Sermon

The Order of Worship (4): The Creed

The Order of Worship (5): Pastoral Prayer

The Order of Worship (6): The Lord’s Supper

The Order of Worship (7): The Benediction