If the liturgy is a dialogue between God and his people, in the Proclamation section God does most of the talking.

God speaks to us primarily through his word–the Bible. The sermon is an encounter with, not just the Bible, but God as revealed in its pages. What we find in the Bible is a collection of ancient texts that were written for us, but not to us. The Bible is a story. That’s not all it is, but it helps us to understand how to approach it. It is not our story, but it is the story in which we live, not just Christians, but all of humanity. It is a story centered on Jesus Christ–the Word as spoken of by John in the first verses of his gospel.

1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

Prayer for Illumination

Rituals are not empty, they are full in the sense that they train us on the deepest level. What sort of training is provided by the weekly repetition of the prayer of illumination? It trains us how to approach the Bible. This prayer is an admission that we need God’s help, to understand what we find in scripture, an admission that we can’t rely on our own reason and knowledge to understand. This is an acknowledgment that the Bible is a book that must be read with spiritual assistance–the Holy Spirit.

This prayer focuses our attention beyond ourselves as readers, indeed, beyond the text to our Lord, Jesus Christ, the Word of God. In this prayer, we anticipate the working of his Grace through our encounter with the text. In a real sense, then, we are preparing for a supernatural event.

The Sunday Prayer of Illumination will change how we approach daily devotions on Monday, for it is a reminder that the words of the Bible are a site of miraculous encounters.

The Sermon

The sermon is, or ought to be, about the Bible.

What is the Bible?

What the Bible isn’t is an encyclopedia, or an instruction manual for life, or a rule book. It’s hard to resist looking at the Bible in these ways because our cultural default is set to view everything as an object that might have a use.

In a recent Tweet, Tim Keller said, “It is impossible to understand a culture without discerning its idols.” This applies to our culture as well. And one of our idols is Reason. Rationalism is the idea that the best, or even only, way to know things is through human reason. Our confidence in human reason has taken some blows in the last century, but we still stubbornly hold onto our faith in it. It is so powerful that it has effected how we read and understand the Bible.

As Christians, we believe that the Bible is true. As Westerners, we believe that truth is an object of human Reason. The Bible, then, becomes nothing more than an object that we study and use as rational subjects. We look for “applications,” instead of implications. We get too wound up about biblical inerrancy. But truth is much bigger than fact or useful information. The Bible becomes something more like an encyclopedia than a story, or a poem, or a painting. As Western Christians we must resist this limited notion of Truth.

So what is the Bible?

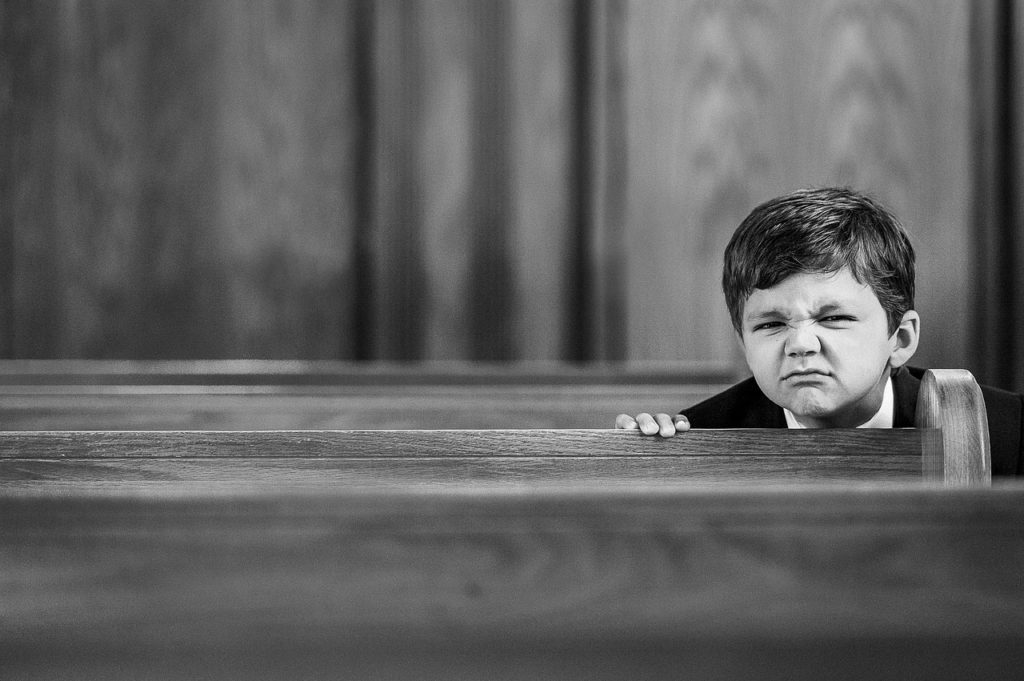

Rather than give a long rational treatise on what the Bible is, let me do what the Bible does and offer a picture of what a sermon, rooted in the Word, can be.

The image is found in Ezekiel:

37 The hand of the Lord was on me, and he brought me out by the Spirit of the Lord and set me in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. 2 He led me back and forth among them, and I saw a great many bones on the floor of the valley, bones that were very dry. 3 He asked me, “Son of man, can these bones live?”

I said, “Sovereign Lord, you alone know.”

4 Then he said to me, “Prophesy to these bones and say to them, ‘Dry bones, hear the word of the Lord! 5 This is what the Sovereign Lordsays to these bones: I will make breath enter you, and you will come to life. 6 I will attach tendons to you and make flesh come upon you and cover you with skin; I will put breath in you, and you will come to life. Then you will know that I am the Lord.’”

7 So I prophesied as I was commanded. And as I was prophesying, there was a noise, a rattling sound, and the bones came together, bone to bone. 8 I looked, and tendons and flesh appeared on them and skin covered them, but there was no breath in them.

9 Then he said to me, “Prophesy to the breath; prophesy, son of man, and say to it, ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: Come, breath, from the four winds and breathe into these slain, that they may live.’” 10 So I prophesied as he commanded me, and breath entered them; they came to life and stood up on their feet—a vast army

We are dry and lifeless. The Word of God, preached by inspired human authors, brings life. God could himself speak directly to the bones, but he chooses an intermediary–Ezekiel. He uses the preacher before us.

This image presents the Word, not as an object that we approach as rational subjects, but as active agent. We are the passive pile of dry bones–we are the object; the Holy Spirit is the subject. He brings life though the hearing of the Word. God is active in the sermon.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”Do we listen to the sermon to learn about life or to receive it? The former is a happy by-product. The sermon is not the reflections of a pastor. It is an act of Grace, and we receive the life that flows from it. #sermon #preaching #liturgy” quote=”Do we listen to the sermon to learn about life or to receive it? The former is a happy by-product. The sermon is not simply the knowledgeable reflections of a pastor. The sermon is an act of Grace, and we receive the life that flows from it.”]

Other posts in this series:

The Order of Worship (1): The Call to Worship and Greeting

The Order of Worship (2): Confession

The Order of Worship (4): The Creed

The Order of Worship (5): Pastoral Prayer

The Order of Worship (6): The Lord’s Supper

The Order of Worship (7): The Benediction