Of course I watched the season 7 premier of The Walking Dead to find out whose head got smashed with Lucille, in last season’s finale. I expected Abraham because he’s too much of a soldier; Rick and company need to be vulnerable in the face of Negan. I was also prepared for Glen because he gets it in the comic books. However, I was not ready to lose both. It was intense emotionally, and gory visually. My twitter feed was full of indignant fans who said, “This time they went too far!”

Of course I watched the season 7 premier of The Walking Dead to find out whose head got smashed with Lucille, in last season’s finale. I expected Abraham because he’s too much of a soldier; Rick and company need to be vulnerable in the face of Negan. I was also prepared for Glen because he gets it in the comic books. However, I was not ready to lose both. It was intense emotionally, and gory visually. My twitter feed was full of indignant fans who said, “This time they went too far!”

Maybe they did, but that’s not what I was thinking about as the credits ran.

I was thinking about the event that actually broke Rick, the event that broke the viewing audience. It’s the central event of the episode that will “change everything”–I was thinking about the near-amputation of Carl’s arm by his own father, called off by Negan at the last second.

This is an obvious allusion to Genesis 22 where God told Abraham, “Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love, and . . . sacrifice him . . . as a burnt offering.” Abraham obediently took Isaac to the place designated for the sacrifice. Isaac, ignorant of the plan, asked his father where the lamb was for the sacrifice. Abraham was evasive and answered that the Lord would provide the lamb. Once they arrived at the site, Abraham bound Isaac with ropes and put him on the stone altar.

Negan makes the same demand on Rick–“Sacrifice your son!” or at least, permanently maim him. We are clearly expected to interpret this scene in, in the light of Genesis 22, so here’s some background.

In Hebrew culture, the first born belongs to God; Yaweh (the Hebrew name for God) has a claim on the first born as representative of the family (Exodus 22, Numbers 3 and 8) — the firstborn’s life is forfeit.

You must give me the firstborn of your sons. Do the same with your cattle and your sheep. Let them stay with their mothers for seven days, but give them to me on the eighth day. (Exodus 22:29-30)

A foundational premise in The Walking Dead, the ancient Hebrews also understood that people were generally guilty of evil, either overtly or in their heart–usually both. The first born, as the representative of the family, bore the guilt of the entire family and belonged to God as payment for this moral debt. God’s demand of the sacrifice of Isaac was simply a calling in of the debt. That’s how Abraham took it anyway.

So Negan is in the position of God, Rick in that of Abraham and Carl, Isaac. It might be said that Rick and his “family” of survivors, owes Negan. In season 6, Rick and a number of Alexandrians carried out a pre-emptive attack on Negan’s people, the Saviors. The reason for the attack is that the Saviors were extorting supplies from the peaceful Hilltop community and Rick expects them to eventually do the same to his Alexandria community, so he proposes the attack. Morgan, assuming the role of moral conscience, opposes the idea.

As evil as the Saviors are, we ought to have been a little disturbed by the nocturnal attack. Rick walks into a room and finds a guy sleeping, and he silently presses a knife into his head. The guy never wakes up. This silent execution is repeated by Glenn and Heath. They admit to each other that they have never killed a living human being. Heath can’t do it, so Glenn murders both in their sleep. The entire Savior outpost is whipped out in two episodes. And we see our heroes do some very questionable things. They aren’t comfortable with them. Carol even leaves the community because she can no longer handle the guilt of these events.

Negan has been wronged and, like the Hebrew God, is simply calling in the debt. In the ancient, eye-for-an-eye legal code, he has a right to an arm and a life–this is his declared purpose for killing one of Rick’s people–which turns out to be two. Both Glen and Abraham were a part of this clandestine first strike on the Saviors.

Although the Abraham of the Bible would have been distressed by the loss of his son, sacrificing Isaac was also an act of giving God his due, but Abraham’s blow never falls on his son. Before he can carry out the sacrifice, angel of the Lord calls out “Stop.”

The demand for Carl’s arm, and the sudden and unexpected revocation of that demand solidly correlates Negan to Yaweh. So what is the point of this allusion?

Is it meant to draw a comparison between the harsh demands of the God of the Old Testament? If this is the case, the writers missed some pretty important elements of the story. Immediately after the biblical Abraham is commanded to stop the sacrifice,

Abraham looked up and there in a thicket he saw a ram[a] caught by its horns. He went over and took the ram and sacrificed it as a burnt offering instead of his son. (Genesis 22:13)

In Genesis 22, God himself provided the alternate sacrifice. The ram functions as a substitute for the first born who is himself a substitute for Abraham’s family. Christians draw a parallel between the ram and Christ who dies on the Roman cross as a replacement for sinners. It’s a story where Grace is at the centre. The God of the Bible transfers the punishment for humanity’s moral failings upon himself. It seems to me, in order to understand this pivotal scene in TWD, we need to look for the substitute, after all, Carl doesn’t lose his arm. What is sacrificed in it’s place? Rick’s strength or defiance is destroyed. Negan can see it in his eyes; Rick is broken.

Negan’s method to achieve Rick’s submission to his will is coercion. Negan threatens to destroy Rick’s whole “family” if he doesn’t comply. God, as represented in both the New and Old Testaments of the Bible, does not use force. Although many elements of The Walking Dead’s season premiere and the story in Genesis 22, and the Gospels is similar, this difference is absolutely key.

To illustrate: Imagine Negan making that whole season 6 finale speech that somebody must die. And he does the “eeny meeny miny moe” thing, and then stops and says,

You are guilty and all deserve death for what you did to my people and what you’ve done to others since the dead began to walk. Rick, don’t you know that human beings were made to do wonderful things in the world. Yeah I know, the zombies complicate things, but they are no excuse. You got distracted from that purpose, Rick. And then you killed people. And I am pissed about that Rick, and someone is going to die because of all the bad stuff you’ve done.

And then he nods and they bring a ram into the circle and smashes its head with Lucille, and they all sit down to a dinner of roast lamb.

A New Testament version would end with:

Remember Rick. You and your people, all people actually, you were made to thrive, not just to survive. I want you to get back on track Rick, start thriving.–because I love you Rick.

But that’s another episode.

The allusion breaks down because Negan isn’t comparable to God regarding righteousness. Negan is far from righteous. Rick has paid for his sins against Negan with the deaths of Abraham and Glen, but, to use biblical language, Negan is still piling condemnation upon himself.

I don’ think the writers of the show are trying to make some statement on the Old Testament God. I think they are making a statement on guilt–Rick’s guilt, and that of his band of survivors. In the world of The Walking Dead, our group of would be survivors might just be a new chosen people, who are called to return to humanity’s purpose. To thrive in the world despite the zombies. I am hoping that the allusion to the interrupted sacrifice of Isaac plays out with a form of redemption for Rick and the rest of the “family” as they seek their lost humanity.

New doesn’t necessarily mean improved.

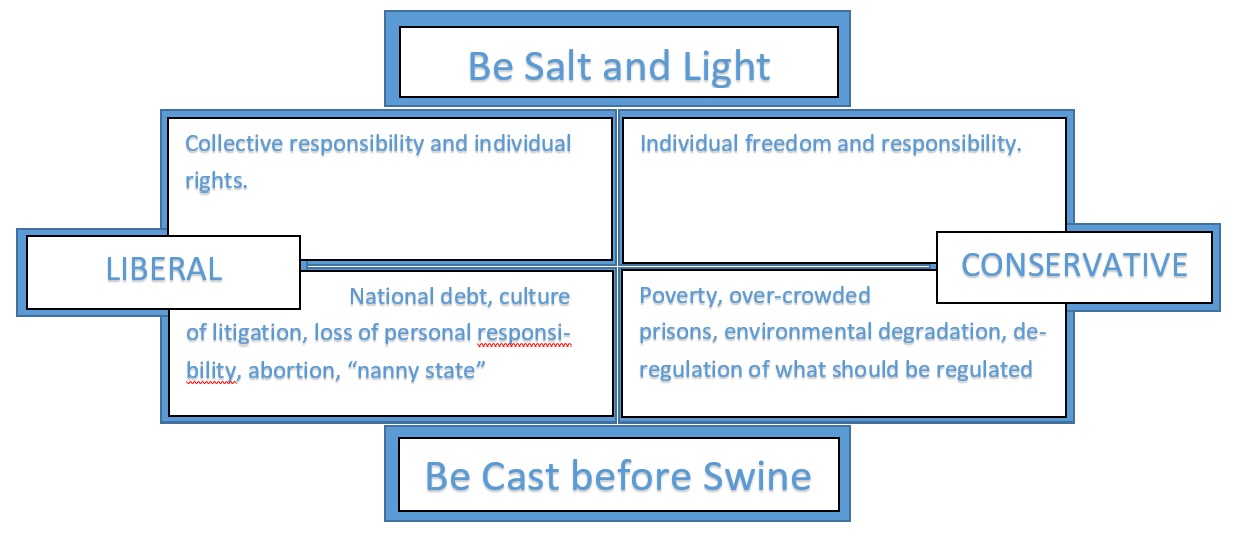

New doesn’t necessarily mean improved. The questions we want to address with the model is, “Liberal or Conservative? How can Christians best be the salt of the world?” So in Johnson’s model we put the two neutral terms on the wings. Christ told us to be salt in the world; he told us that we are to season, preserve and heal the world. He also said that if we aren’t salt, we would be cast before swine. Serious stuff. On the model I have placed where we are headed, the “Higher Purpose” above and at the bottom, the “Deeper Fear,” or what lies in the opposite direction of the higher purpose. All Christians, both liberal and conservative, have the same higher purpose and the same deeper fear.

The questions we want to address with the model is, “Liberal or Conservative? How can Christians best be the salt of the world?” So in Johnson’s model we put the two neutral terms on the wings. Christ told us to be salt in the world; he told us that we are to season, preserve and heal the world. He also said that if we aren’t salt, we would be cast before swine. Serious stuff. On the model I have placed where we are headed, the “Higher Purpose” above and at the bottom, the “Deeper Fear,” or what lies in the opposite direction of the higher purpose. All Christians, both liberal and conservative, have the same higher purpose and the same deeper fear.