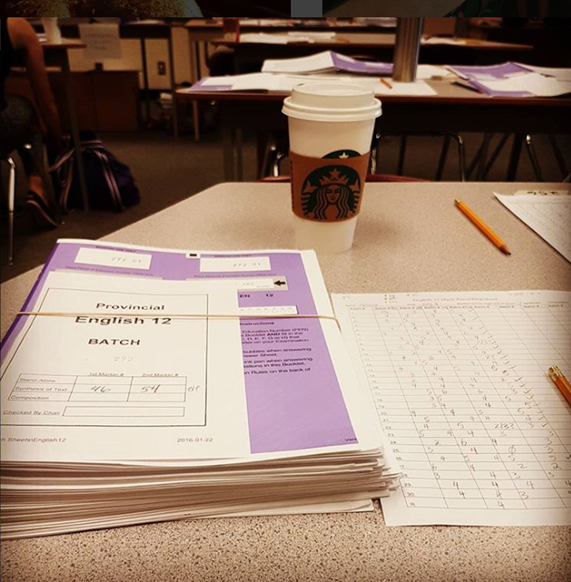

The view of an exam composition marker

Of course you want the highest mark possible on your exam composition.

I’ve been marking the BC English 12 provincial exam for many years—more than 20, I think. I just finished marking the composition for this year’s exam and I decided to write about it while my thoughts are still fresh.

The best way to get a 6 out of 6 on your composition on the English 12 exam is to be an excellent writer. Not everyone is an excellent writer. But there is much an average writer can do to give them a chance to earn the highest score of which they are capable.

Here are what I consider the 12 most important things to keep in mind when writing Part D: The Composition.

1. It’s all about conflict.

If you write a narrative, and I recommend that you seriously consider writing a narrative, focus on the conflict.

Don’t start your narrative with the alarm clock ringing. This is a very short composition, you don’t have time to lollygag–don’t write about life, write about conflict!

2. Don’t be like everyone else!

Markers read a lot of compositions—well over 700 per day. All have been written by English 12 students and are based on the same prompt. This can lead to a lot of “sameness”—same diction, same topics, same perspective, same approach, same structure. It feels like you are reading the same five essays, hour after hour, day after day.

It stands to reason, then, if you can write an exam composition that is not like all others, yours will stand out. Most of my 12 keys are about how to make your composition stand out, in a good way.

3. Go with your fifth idea.

If the composition prompt is, “Beauty can be found in simple things,” do not write about smiles, snowflakes, kittens, rainbows or babies. Everyone is writing about these things because they are the first things that pop into their minds. The solution is, don’t write about the first thing that pops into your mind—or the second. Get down your list. When you get to oatmeal, socks or the word “and”–you have arrived. I’m excited just thinking about an essay about the word “and.”

When the prompt was, “Surprises can make life more interesting” – over 90% were about surprise birthday parties. Because of the lack of surprises when they opened the exam book, markers were ready to jump off the buildings by the middle of the first afternoon.

Oh, and don’t think that you are original if you argue that surprises don’t make life more interesting—negation of the prompt is not clever, it’s cliché. Speaking of clichés . . .

4. Don’t use clichés.

No matter what the prompt is, markers can always count on frequent encounters with all of the following:

“When life gives you lemons, make lemonade”

“Life can throw you a curveball . . .”

“Life is a rollercoaster full of ups and downs.”

“Life can hit you like a tonne of bricks.”

“Life is like a box of chocolates . . . .” This one always includes the appropriate textual or parenthetical citation.

By using clichés, you are screaming to your reader that you are an average writer, at best. And you may be an average writer, there is nothing wrong with that, but there is no sense advertising it. And who knows, if you are deliberate about not using clichés, you just might infuse a bit of freshness that gives your exam composition a boost.

5. Don’t write about death.

It feels like at least a third of the compositions are about death. As markers, we are forced to vicariously experience the death of every family member in every possible combination from every possible disease. Then there are the accidents, usually car accidents. These often involve drunk driving and the loss of a best friend or lover. Markers don’t like death essays, not because it makes the process too difficult emotionally. Quite the opposite, in fact.

I am pretty sure that many English 12 teachers encourage their students to write a composition that is “emotionally engaging.” This is not bad advice, but when students hear the words “emotionally engaging” they instantly settle on the death of a loved one, because they can think of nothing else that produces stronger emotions than the death of a loved one.

This is probably true, but most high school students lack the skill to sensitively deal with topics like death. Consequently, these “death essays” become cliché, which is the opposite effect you are trying to achieve. Save writing about death for when you are a more experienced writer, and you have longer than an hour and a 600-word limit.

6. Don’t preach.

Nobody wants to be preached at. This is a “stance” issue. Readers don’t like to be talked down to. As a marker, I’ve been preached to about recycling and about how I should be Christian, and about why all religions are dumb. I’ve been told repeatedly that I need to be tolerant. I’m sick of lectures instructing me how to face the hardships of life and how I should respect the elderly. I now know what I should think about every issue imaginable.

You can still write about these things but take a different stance—write about when you discovered the importance of recycling. Or how faith adds meaning to your life. Write about a difficulty that you experienced and what you learned from it. See the difference? Rather than tell me what I should do and learn, talk about what you did and what you learned.

7. Have a strong first paragraph.

Many first paragraphs read like the students are warming up for the real task of writing the essay. They throw down their first thoughts on the subject searching for the point from which they can push off into the first paragraph of their composition. The warm-up or the search for a point of departure should happen someplace else. Write for a few minutes on a piece of scrap paper till you find your direction, then carefully craft the first paragraph to set up what is to come. The reader makes all sorts of judgments from the first lines of your composition; first impressions are powerful—make a good first impression.

I have found that many student compositions benefit from simply drawing a line through the first paragraph.

I’ve read compositions that use “the word” five times in the introduction. If the prompt tells you to write about beauty or surprises, challenges, maturity, change, dreams or relationships, consider not using that word in the essay at all. Or if you do use “the word,” use it in the last line of the composition. As with all creative writing, it is better to show than to tell.

8. Be Specific.

Generalities are boring.

This is true for everything you write be it an email, an essay or a narrative. Don’t say, “We went out for my favourite meal,” say, “We went out for chicken wings and Shirley Temples.” Don’t write, “My boyfriend pulled his car into the driveway”; have him pull up “in the family mini-van” or “his red convertible,” or his “1978 windowless van with the words ‘Refer Madness’ airbrushed on the side.” Specifics make a difference. If you don’t believe me, ask your father.

9. Don’t write a “5 paragraph essay.”

First of all, by the time you are in grade 12 you should never write a 5 paragraph essay (although there is nothing wrong with an essay of five paragraphs). The body of a 5 paragraph essay consists of 3 examples from your life that show the prompt to be true.

So if the topic is something like “Certain situations lead to maturity,” don’t write an essay in which you briefly and superficially discuss three of the following:

- entry into kindergarten,

- the magic of puberty,

- your parents’ divorce,

- a torn ACL,

- getting a driver’s license,

- your first job,

- or first kiss,

- the death of a loved one,

- or moving to, or within, Canada.

Pick one of these (except the death of a loved one) and meaningfully explore the factors and forces that contributed to your maturation.

You understand, of course, that by adding or dropping a paragraph to the essay I’ve just described does not fix the problem.

10. Punctuation, spelling and capitalization, etc.

There’s no avoiding the fact that the mechanics of writing are important. The good news is that all of the writing on the exam is marked as a first draft, so if you misspell the odd word, or miss a comma or two, your mark will not go down.

So it doesn’t matter if I don’t know the difference between “then” and “than”? Or “there,” “their” and “they’re”?

Technically no, but no upper-level writer will ever confuse these words. So by confusing them, you are proclaiming, loudly, that you are not an upper-level writer.

Work hard to understand basic usage and punctuation rules.

As for spelling, two words that, for some reason, come up again and again in the composition essays are obstacle and opportunity. For years I’ve been telling my students to make sure they can spell these two words correctly—because “obsticle” and “oppertunity” scream out that you may not be a competent writer.

11. Be yourself.

You are not a 47-year-old drug addict living in Detroit.

You are not a soldier storming the beaches of Normandy.

You are not a mother deer concerned about your fawn.

Like death, this sort of writing requires a maturity of thought and style that most young writers don’t have.

The thing is, you are the preeminent expert on one subject–YOU. You know things about this topic that no one else does. Play to your strengths. Human beings, even markers, respond to stories–good stories, well told. I recommend that you walk into your exam with three stories, true stories. If it’s a true story, you can draw from an actual setting with actual characters doing actual things (and you can embellish a little). And don’t just tell me what happened, tell me what you thought and felt as well. But go even further–What did this event mean? How did it change you? You may never have thought about it, but think about it now. This type of essay is generally called a personal narrative. It involves a true story and some reflection about what the story means. Consider practicing these three stories beforehand. Then, when you see the prompt, adapt one of them to fit. Or write a brand new one if you are so inspired.

So, for these reasons, I strongly recommend you write a personal narrative for your exam composition.

12. “In Conclusion”

Don’t end the last paragraph of your exam composition with the words, “in conclusion.”

In conclusion, I must tell you that I’ve read papers that have ignored half of my 12 keys to writing a great composition and they still earned a 6 out of 6. They did so because the authors are great writers, but these 12 keys will give you your best chance at earning the highest mark of which you are capable.

I hope you read this post long before you take your exam–years preferably–because all of these things take practice. Good luck, and I look forward to reading your Composition.

Is there any other advice you give your students?

What else has your teacher suggested for writing the composition?

See also: How to Write the Synthesis Essay.