jplenio / Pixabay

I have this theory about monsters and what they mean.

Although they are antagonists, they are not the same as villains. They are much more interesting. Heroes are about what we want to be. Villains are what we don’t want to be. Monsters are what don’t want to be, but we might be anyway whether we like it or not.

Heroes and Villains

Heroes are our ideal. They represent our best selves. They stand for what we want to stand for as a group. They have the characteristics that we value, and wish we had more of. Heroes are always courageous because this is a universally admired characteristic. Heroes tend to defend the innocent and the collective good. We normal humans don’t always do these things, but we like to think of ourselves type of person who would. We project all this awesomeness onto our heroes.

Our heroes change because we change. The great hero Beowulf bragged about his heroic exploits. Today, we’d find his sort of arrogant pride to be villainous, but Anglo-Saxon listeners loved boasting if you could back it up. When the great Achilles wasn’t harvesting Trojans, he could be found weeping by the seashore. For Greek audiences, this wasn’t a sign of weakness, but passion–a virtue, until he took it a little too far; the Greeks also liked a tragic flaw.

Villains are the opposite of heroes. They have qualities and characteristics that we castigate. Villains break promises or they are cowards or they threaten the lives of the innocent and the virtue of women. They possess the characteristics for which we punish our children. Not all otherness is a threat. Villains represent the bad side of “otherness.”

And so we have a fence around our identity. Within the fence, we find our people and the values we espouse. What lies outside the fence is otherness–other people and the values that we don’t hold, some of which we reject.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”Heroes are how we see ourselves, villains are the opposite, and monsters represent the nasty bits of ourselves we’d rather not admit to. #Heroes #Villains #Monsters ” quote=”Heroes are how we see ourselves, villains are the opposite, and monsters represent the nasty bits of ourselves we’d rather not admit to. “]

Narrative Identity

Philosopher Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005) describes the relationship between narrative and identity suggesting that when we tell our stories, we are clarifying our identity. Stories constitute the identity of individuals, but the mechanism is the same for collective identities.

Ricoeur suggests that identity is revealed through the interplay of two competing forces within narratives. The first force presses on the narrator to represent his role in the story in a way that is consistent with his view of himself—this Ricoeur calls the “demand for concordance.” We like to think of our identity as having some permanence, so we are compelled to tell our stories in a way that is consistent with this idea we have of ourselves.

The second force at work in the recounting of past events is what Ricoeur calls the “admission of discordance.” This force presses the teller to accurately represent himself in thought, word, and deed.

These two forces are not always in concert. Sometimes how we think of ourselves is inconsistent with reality. A small divergence can be easily suppressed, but small divergences can build up and large ones are not easily ignored. The discordant force threatens the supposed permanence of the teller’s identity. The competition between these stories can create tension in our narratives. It is out of this tension, says Ricoeur, that his identity is shaped and expressed.

Let me tell you a personal story that which illustrates this dynamic.

A True Story

When I was around 19, I went to a midnight movie with three friends, Jim, Marylou, and Stewart—I think the movie was Animal House. After the show, I stopped briefly to chat another friend in the theatre lobby, so I left the theatre alone a few minutes later. As I stepped outside, four guys in an old car aggressively pulled up to the curb and, completely unprovoked, flipped me the bird. Without thinking, I responded in kind, then turned to walk down the dark alley in the direction of the car.

I sensed that I might be in some danger when I heard the car doors slam behind me. I knew they were coming when I heard the sounds of pursuit behind me. I picked up my pace, just a little. I didn’t need to go any faster because I saw that I would make it around the corner before they caught me.

My friends were ready. Jim had already told MaryLou to get into the car and lock the door. He stood leaning against the car, waiting. Stewart had taken off his jacket and was lighting a cigarette. I don’t know how they knew what was happening but, I was glad they did. I turned and prepared to meet the threat, with fists if necessary. It’s all we had, and I hoped it would be enough.

My would-be assailants, thinking they would catch a vulnerable victim, rounded the corner at a run, eager for blood. When they saw that it was going to have to be a fair fight, they slowed to a walk, nodded, said “Hey,” and kept walking past us.

The Demand for Concordance

I’ve told this story many times, and it’s the same every time. When I analyze these events, it’s not to hard to find some tension between the demand for concordance and the admission of discordance.

I think of myself as a nice person and a peacemaker. I am good at navigating around conflict. In my recounting of the above story, I suppressed those little things which were inconsistent with this identity as I saw it. I didn’t really behave like a peacemaker when I returned the obscene gesture, but I soften this inconsistency by describing my attackers as aggressive and my role in this altercation as, merely unthinking. But there is an even more powerful challenge to my identity than the one against my peacekeeping ideals.

Am I a coward?

In my narrative, there is no mention of the fear I felt at the time, but I was scared. This omission is a result of my reluctance to admit the possibility of cowardice. I don’t remember if there were four or three attackers, but I went with four because it excuses the fear that still clings to this memory. In the retelling, I emphasize that I picking up my pace was strategic, and not out of any fear. Their unwillingness to fight even with numerical superiority transfers cowardice onto them. Lastly, I don’t know if Stewart calmly lit a cigarette and, although I think Jim leaned against the car, I’m not sure he was that casual. These details suggest a calm in my friends, which is transferred to me by association. I also remember trying not to hurry, but was I as successful as my story recounts? There is no lie here, just nuance that comes from the demand that my story concords with my held identity.

It is conceivable that new experiences would reveal that I was not a peacemaker, or I was in fact, a coward. If this turned out to be true it would have gotten harder and harder to admit this discordance relative to me self-understanding.

This can happen on a collective level as well.

Here is where the monsters come in.

When Monsters Attack

Monsters show up–with any kind of strength–only under particular circumstances—when our collective identity is in crisis. When the stuff we’ve been suppressing begins to create weak points in the boundaries between the “us” and otherness. The monster is what prowls around the fence and attack it at its weakest point. The weak points of our identity are those places in the boundaries of our collective identity where we begin to lack certainty about who we are. The parts that are getting harder to suppress. Discordance that is beginning to demand admission.

The fascinating thing about monsters is they don’t simply represent otherness. This is too simplistic. Monsters are the projection of uncomfortable possibilities. The monsters that intrigue us, the ones that, again and again, find their way into our stories, are the ones that most directly challenge our understanding of ourselves. By their very presence, they ask us the questions that, deep down, we have already been asking ourselves—Is this really who you are?

[click_to_tweet tweet=”The hero is what we are, or at least want to be. The villain is what we are not. Monsters are the embodiment of what is perhaps the truth that we want to suppress. They appear as the suppression begins to fail. #Monsters #Heroes #Villains” quote=”The hero is what we are, or at least want to be. The villain is what we are not. Monsters are the embodiment of what is perhaps the truth that we want to suppress. They appear as the suppression begins to fail.”]

Our Monsters

The Greek’s had the Minotaur and Medusa. The Anglo-Saxons told stories about the monster of the moors and marshes, Grendel and dragons. Demons and witches terrorized the medieval identity. Later came Frankenstein’s monster, the Wolfman, and the vampire who attacked the boundaries of Modern identities.

Each of these monsters terrorized a particular cultural identity that was in crisis. If Anglo-Saxon storyteller had conceived of Frankenstein’s monster and, the next night in the mead hall, told his story about a creature made from corpses, he’d receive an awkward silence and some puzzled grunts from his Anglo-Saxon audience. Such a monster would not have intrigued them, and the first telling would also have been the last.

Monsters scare and fascinate a people because the monster is tailor-made for that culture. Its form is the embodiment of particular doubts about who we are. It attacks the fence that surrounds our identity at exactly the point where it is the weakest. This is why we can learn a lot about a culture by studying its monsters.

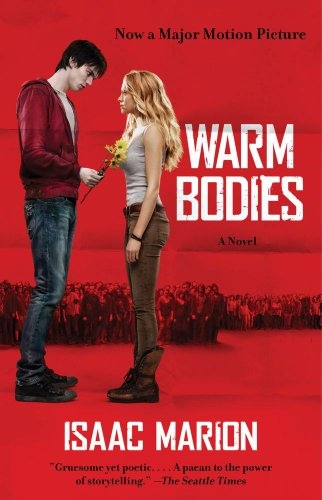

This is why we can learn a lot about ourselves by studying our monster—the zombie horde.

A manufactured object obviously has a purpose that was built into it by its designers, but a lot of people do not believe this is true for human beings.

A manufactured object obviously has a purpose that was built into it by its designers, but a lot of people do not believe this is true for human beings.