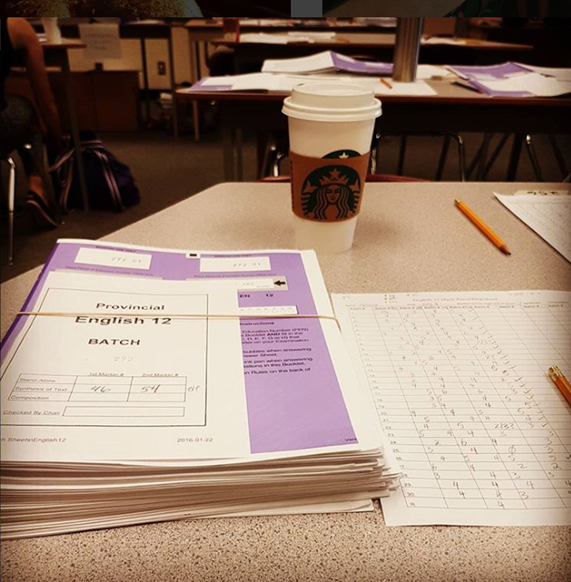

Wokandapix / Pixabay

I just finished a weekend of marking the brand new Literacy 10 Assessment–brought to you by the Ministry of Education in British Columbia.

As I read through hundreds and hundreds of student compositions, I wanted to talk to the students that wrote them, or their teachers and tell them if only they did this or that little thing, they’d get a far better score. There are some pretty simple ways you can get better results on this assessment.

Why do well?

But before I get into how to do well, perhaps we’d better talk about why. This is not one of those “high stakes exams” we hear about. One of those that determine if you get into university or how much funding your school gets. This doesn’t have that kind of baggage–that’s a good thing. The response of the narrow minded is “then it doesn’t matter.” This is absolutely correct if having an accurate assessment of one’s reading, writing and thinking does not matter.

If students do their best on this assessment, the results will provide them with some valuable information about what they are good at and what they can work on over the next few years to improve important competencies. Competencies that, once developed, will certainly be personally relevant. This is not an English test, it is about literacy–the skills it assesses transcend English class, and reach beyond high school graduation.

The Structure of the Literacy 10 Assessment

Part A

Students are given a selection of texts. These include graphs and diagrams as well as as various passages including narrative and expository. Students will answer a variety of questions on these texts–these are not typical multiple choice, but a variety of forms that break the mold of traditional assessments.

There are two writing tasks in Part A. A Graphic Organizer and a Critical Response.

This section is called “What They Say” in that students write about what other people say about a topic.

Part B

This section is called “What I Say” because here students are invited to enter into the conversation. Students can chose between Literacy for Information and Literacy for Expression. Each of these have readings and a prompt for an essay.

How to do well.

Tip #1 — Understand the task.

There are three writing tasks on this assessment. The Graphic Organizer, a Critical Response and Writing for Information/Expression. The expectations for each task are very different, so students must understand which task they working on.

- Graphic Organizer — Here the student is expected to organize ideas found in texts. They will organize ideas one a graphic organizer–a table, a pyramid, a Venn Diagram, etc. Here they show an understanding of cause/effect, coordinate and subordinate ideas, explanation/example, etc. Students are asked to make assertions and briefly explain.

- Critical Response — This section is nicknamed “What They Say.” This is a multi-paragraph response. For clarity’s sake, let’s call it an essay. Students must have more than 1 paragraph. Technically 2 is fine, but I suggest a minimum of 3. Write an intro that ends with a thesis statement–be explicit. A minimum of a one-paragraph body that starts with a topic sentence. And a conclusion. Most students should try for two or three body paragraphs. Again, this is “What They Say”; The instructions say, “With reference to one or more of the texts.” Students should show they’ve read the texts. This is important: students don’t offer their thoughts or ideas here–their task in this section is to clearly communicate what others are saying. Students should write about the texts–not about what they think or know. This is not a personal response, that comes later.

- Literacy for Information or Literacy for Expression — This section is nicknamed, “What I Say,” and it offers students more freedom in what they say and how they say it–they may write an essay, or a story, or even a poem. In this section, students are given a prompt to which they respond in writing. Readings accompany the prompt. Students may use these as inspiration for their own writing, but there is no requirement that students refer to them. It is important that students answer the prompt and not allow the readings to pull you off of this task. Tell students to dare to be different–write a story, use dialogue (but know how to format it). Show their insight and creativity from the first line!

Tip #2 — Be Specific

For all of these tasks, be specific, not general. Clear, not vague. Make sure the support is relevant and specific. Back up all of your assertions with specific evidence or examples.

Tip #3 — Give Students a Word Count

For some reason, the creators of the assessment are very reluctant to give students a word count. I don’t know what the reason is. Anyone who has taught grade 10 students knows that most will write a one-sentence answer to any question unless specifically told to write more. Then most a quite willing to comply. This will also the case on the Literacy 10 Assessment–if they write a 50-word response to any of the essays, they will do poorly, and there is no need for this.

For the Graphic Organizer, don’t over-write. The exception is the Graphic organizer. Two sentences per box will be fine. A quote doesn’t hurt, but it is not necessary.

For the essays tell students that they should write a minimum of 300 words. A 600 word response is completely appropriate.

Tip #3 — Exceed Minimums

When then instructions say, “With reference to one or more of the texts,” refer to at least two. When the instructions say multi-paragraph, write at least 3. Exceed minimums, but don’t get carried away–don’t refer to all the texts multiple times and don’t write a seven paragraph essay. Good writers know when their point has been made and don’t need to compensate with volume.

Tip #4 — Read for Main Ideas

Most of the tasks in the assessment revolve around picking up on the main ideas for each text. Students should practice this in their classes, and they should focus on this as they read the passages on the assessment.

Tip #5 — Capitals and Periods

I’ve marked provincial exams for more than two decades, and have always been baffled as to why so many students consider the caps and periods optional, as if they were some sort of stylistic device that only pretentious professionals employed.

If you know what a sentence is. Show that you know.

If you don’t know what a sentence is, toss a few periods and capitals into your writing. It can’t hurt. At least the assessor would get the idea that you’re trying.

Tip #6 Refer to Texts by Name

And put this name in the proper format.

Tip #7 — Read It Over

Typos and spelling mistakes don’t leave a very good impression. Ideally, every spelling and grammatical error that remains in each composition should only be the ones the student is not aware of. If they know how to spell “environment” they should not allow “emviromint” remain uncorrected in their essay.

Tip #8 — Paragraphing

Reinforce the importance of paragraphing to your students. It shows the students understanding of structuring writing, and it makes their writing easier to understand.

So, topic sentences, specific evidence with explanations, and transitions will really boost those marks. It’s fine if students don’t write in paragraphs, but only if they legitimately don’t understand paragraphing. That’s one of the things we are assessing.

Tip #9 — Answer the questions even if it’s not relevant to you.

Sometimes students will be asked to give a personal opinion or reflection to an issue or an idea. They need to put some effort into this, even if they honestly don’t have an opinion, reaction or to describe something they learned or how their opinion has shifted. They should explain why they don’t have an opinion, or talk about an opinion that a student might have. A specific response in these cases can bump students up a mark.