Everybody whines and complains on occasion. It can be how we process disappointment. Some, for one reason or another, whine and complain all the time. This can be a defense mechanism; “If life is going to suck anyway, I might as well anticipate the disappointment.”

In “Greenleaf,” Flannery O’Connor describes the perpetual victim and provides the antidote to this poisonous view of oneself.

The Perpetual Victim

Mrs. May, protagonist of “Greenleaf,” declares, “I’m the victim. I’ve always been the victim.”

Mrs. may owns a small farm and she believes it functions entirely by her efforts and hers alone. She declares to her city friends,

“Everything is against you, the weather is against you and the dirt is against you and the help is against you.”

No wonder she considers herself a victim, if she thinks weather and soil are her antagonists. She is blind to the fact that without weather and dirt, there is no farm—these things aren’t adversaries; they are gifts. And so is the help against which she rails—the help is Mr. Greenleaf.

The narrator tells us that Mrs. May “had set herself up in the dairy business after Mr. Greenleaf had answered her ad.” Mr. Greenleaf‘s arrival precedes the establishment of the farm. Good thing too, because he is the reason her farm is as successful as it is.

This is not, at first, apparent because the third-person narrator tells the story from Mrs. May’s perspective and is, therefore, not to be trusted. For instance, when the narrator reports a field had come up in clover instead of rye “because Mr. Greenleaf had used the wrong seeds in the grain drill,” we are receiving Mrs. May’s interpretation of reality. Mr. Greenleaf likely ignored her instructions because he knew better.

Mrs. May frequently speaks of how hard she works. She believes she “had been working continuously for fifteen years” and that “before any kind of judgement seat, she would be able to say: I’ve worked, I have not wallowed.” Interestingly, she doesn’t do a stitch of actual work through the whole course of the narrative. Conversely, Mr. Greenleaf is always occupied with farming tasks.

Everything Mrs. May has, comes to her through the created world and her good fortune at the arrival of Mr. Greenleaf. But she doesn’t see any of it. She places a high value on her own, relatively insignificant, efforts and a correspondingly low value on the many undeserved blessings she has received.

Mrs. May’s Faith

Two quotes will suffice to give us the state of Mrs. May’s faith:

“She was a good Christian woman with a large respect for religion, though she did not, of course, believe any of it was true.”

“She thought the word Jesus should be kept inside the church building like other words inside the bedroom.”

Symbolism

Mrs. May seeks no relationship with God and her rejection of Grace is shown through various symbols.

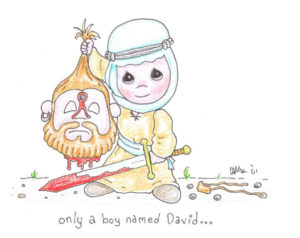

A stray bull has arrived on her place. In the opening scene, he is compared to a Greek God, complete with a wreath upon his head. He stands beneath her window like a bovine Romeo. Not only is this an allusion to Shakespeare’s play, it is also a reference to Zeus who, in the form of a bull, rapes Europa. When the wreath “slipped down to the base of his horns . . . it looked like a menacing prickly crown.” The bull has become a symbol of Christ. Mrs. May’s view of this transcendent visitor is far more terrestrial–“an uncouth country suitor.” As a symbol of Jesus, the bull is persistent in his pursuit of Mrs. May. She consistently tries to get rid of him.

Another symbol in the story is the sun. Among these is the “black wall of trees with a sharp sawtooth edge that held off the indifferent sky.” The sun, a symbol of providential grace, is blocked off from Mrs. May’s property. In one of her dreams, “the sun [was] trying to burn through the tree line and she stopped to watch, safe in the knowledge that it couldn’t, that it had to sink the way it always did outside her property.” Her dreams reflect her stance toward God and his gifts.

The symbolism of the bull and the sun as two figures of the Trinity some together in description of Mrs. May’s view out her window.

The sun, moving over the black and white grazing cows, was just a little brighter than the rest of the sky. Looking down, she saw a darker shape that might have been its shadow cast at an angle, moving among them.

The “shadow” is the bull, a manifestation of the sun on this side of the impenetrable trees. Mrs. May lives in rejection of God and all his gifts. She believes herself to be self-sufficient and autonomous.

Lillies of the Field

The Greenleafs, on the other hand, absorb grace in all its forms. The name is suggestive of their familial attitude toward grace, for green leaves soak up the sun and flourish. When Mrs. May takes a trip out to the farm belonging to Mr. Greenleaf’s twin boys, the “the sun was beating down directly” onto the roof of their house. Their milking parlor “was filled with sunlight” and “the metal stanchions gleamed ferociously.” By contrast, from Mrs. May’s window the sun was “just a little brighter than the rest of the sky.”

It is not accident that both Mrs. May and Mr. Greenleaf each have two sons. In this way O’Connor can compare the generational affect on rejection and acceptance of Grace. The May boys are as unhappy and resentful as their mother. The Greenleaf boys are flourishing.

It is because they are flourishing that Mrs. May resents the Greenleaf’s. She means it as criticism when she says, “They lived like the lilies of the field, off the fat that she had struggled to put into the land.” Here we see that she takes credit for God’s gifts, and she derides the Greenleaf’s for living out Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 6:28,

And why do you worry about clothes? See how the lilies of the field grow. They do not labor or spin.

Once, Mrs. May flippantly says, “I thank God for that.” Mr. Greenleaf sincerely responds, “I thank Gawd for every-thang.” He lives out the Biblical injunction to “give thanks in all circumstances, for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus” (I Thessalonians 5:18).

Victimhood and Gratitude

Mrs. May was so ungrateful for her undeserved blessings that she poisoned herself and her two sons. She created a false reality where Mr. Greenleaf was a parasite feeding off of her family.

O’Connor’s point with Mrs. May is to show that a denial of grace necessarily leads to ingratitude and resentment. Mrs. May’s life is defined by ingratitude, but she is blind to this failing. Ironically, while lecturing Mr. Greenleaf on the supposed ingratitude of his sons, she says, “Some people learn gratitude too late . . . and some never learn it at all.” She doesn’t know that she’s speaking only of herself.

The cure for Mrs. May’s form of perpetual victimhood is gratitude. Unfortunately for her, Mrs. May’s ingratitude and victimhood is terminal. She never receives the cure, although in the moments before her death, she does see what she’s been missing her entire life.

She continued to stare straight ahead but the entire scene in front of her had changed—the tree line was a dark wound in a world that was nothing but sky—and she had the look of a person whose sight has been suddenly restored but who finds the light unbearable.

As she dies in the unbreakable embrace of the bull’s horns, she sees the insignificance of the tree-barrier that separated her kingdom from God’s.

I love these

I love these