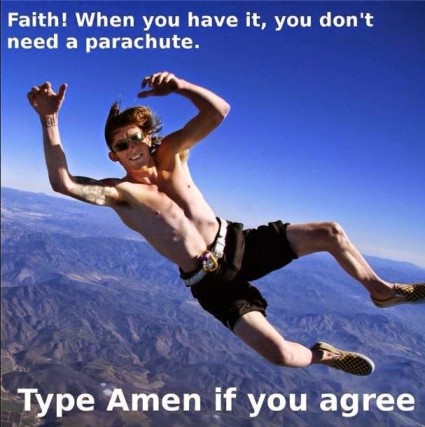

This was an image on Facebook.

It portrays a popular understanding of faith. It describes what we might call blind faith. The adjective blind distinguishes this faith from reasonable faith–or simply, faith.

Faith versus Reason

There is a popular, but mistaken, notion that religious people base their conviction of the existence of God on a faith that is opposed to reason. I am mildly frustrated when I read this error in an online rant from some guy trying to prove religious people are idiots because they are so irrational. But what really drives me nuts is when Christians to it. Both the atheist and the theist are mistaken when they think faith is the opposite of reason.

The Importance of Reason

Reason is really important. It is important that Christians are reasonable. Without reason, faith will become nothing more than sentiment. The more sentimental faith becomes, the more it will be pushed around by the values of the dominant culture, or some mutant form of Christianity.

Christians need to understand that reason is not a bad thing–God made it. It is important that we clarify terms.

What Reason is Not

Luigi Giussani’s in the second chapter The Religious Sense discusses what reason is not.

- First, rational is not the same as demonstrable. This is the empirical approach which says that a thing is true, only if we have evidence. (I will point out that this principle itself is not empirically verifiable, so empiricism is self-refuting as a complete theory of knowledge.) There are many things that are rational, that are not demonstrable.

- Second, rational is not the same as logical. Logic is all about coherence. It is logical to say, as my son once did, that creatures eat what they like; beavers eat trees; trees taste good. It’s logical but based on a false premise–not rational.

Logic and demonstration are two of the tools in the hands of reason. Reason, as it has been understood for millennia, and as it is lived by every human being who has ever lived, is much bigger than the merely demonstrable or logical.

Giussanii says that rationality is adherence to reality, and because reality is so very big and deep and wide, rationality is a lot bigger than we often think. There are different procedures for using reason–all depend on the object.

- It is rational to say that water is H20. My certainty comes from a scientific or analytic procedure.

- It is rational to say that (a+b)(a-b)=(a² -b²) The procedure here is mathematical.

- It is rational to say that a woman has the same rights as a man. This claim is based on a philosophical approach: all humans are equal; women are human; women are equal to men.

- It is rational to say that my mother loves me. This moral or existential certainty is derived from many thousands of encounters with my mother.

Importantly, we can be in error when using any of these methods. But we will always be in error–we will be irrational–if we use the wrong procedure. The method one uses is dictated by the object. It would be irrational of me to attempt to use the philosophical procedure to attempt to understand the chemical composition water. It would be equally irrational to use the scientific procedure to determine a mother’s love for her child. When I sit down to dinner at my mother’s house, I do not need to test the food to know that the food isn’t poisoned. It’s irrational for me to think it is. It would be irrational to have to test each component of the meal in order to ascertain that it was safe for consumption.

We aren’t being rational if we are limiting reason to only two or three categories.

A Definition of Faith

Now for a definition of faith.

When we are not talking about blind faith, we are talking about faith in relation to reason. Giussani’s definition of faith is “adhesion to what another affirms.” Faith is unreasonable if there are no adequate reasons for the faith.

I have reasons to adhere to what my doctor tells me about exercise. I have reasons to believe what others tell me about the molecular composition of water. I have reasons to believe in the eyewitness accounts of Christ’s resurrection. Faith is reasonable if there are reasons to adhere to what another affirms.

Imagine if humanity never practiced this type of reasonable faith. We’d never move forward because each individual would need to start at square one. I’d have to study the effects of exercise on the cholesterol levels myself. We’d never get anywhere as a civilization. So, I accept it as true and act accordingly. It’s rational to do so, because I have good reason to believe it to be true. So even the knowledge made certain by the first three methods require faith.

Perhaps these definitions of faith and reason are still unacceptable to some, but these are the definitions that human beings live by–they are the definitions most attuned to the reality of lived experience. If one lives by them, one can be said to have a personal relationship with reality.