What’s the difference between carpe diem, YOLO, and the Christian view of “seizing the day”? We consider C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters–the demons want our focus to be on the future.

What’s the difference between carpe diem, YOLO, and the Christian view of “seizing the day”? We consider C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters–the demons want our focus to be on the future.

First, an analysis of Robert Herrick’s “To the Virgins” and Andrew Marvel’s “To His Coy Mistress,” and then the difference between carpe diem, YOLO (You Only Lie Once), and Christian carpe diem. We consider C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters–the demons don’t like us to “seize the day.”

Creative Non-Fiction is a great genre for school writing. Every year I assign a creative non-fiction essay to my students. In this video, I read, and talk through some of the processes involved in composing the essay called “Coffee and Conscience.”

Should we read Fairy Tales to our children? Can Christians read Harry Potter? This video is about the relationship between faith and fantasy.

This video concludes the discussion that fairy tales offer us a true picture of reality. They show us the effects of the Fall and an almost universal desire for Redemption and a happy ending:

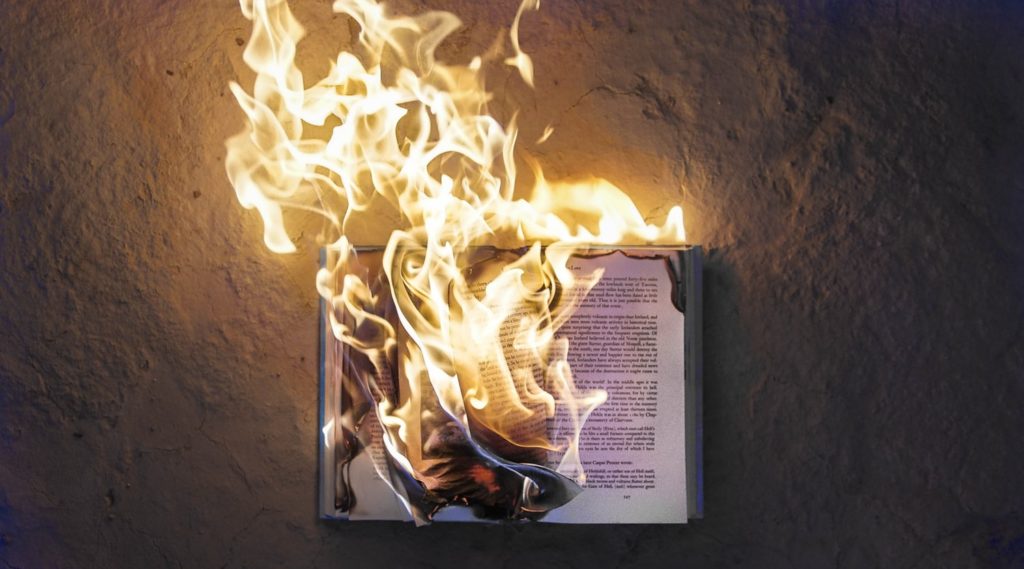

Photo by Fred Kearney on Unsplash

I am doing a “Banned Books” unit in my English 12 class this year.

The idea came to me when I heard that it was Banned Books Week (this year, September 22-28). This is an annual religious festival in honour of one of our culture’s main deities–Freedom. More particular, we celebrate the freedom to read. Because, in some circles, to challenge a book is to challenge a god, the celebration can sometimes take on a “screw you” sort of tone. But this is a worthy focus week, even for those for those who don’t bend the knee to freedom, for there are worrisome current and dangerous historical attempts to censor books in libraries and schools. These are often attempting not just to protect the vulnerable but to limit thought. Most of the books on the banned books lists were not, in fact, banned but challenged by someone somewhere about the use of these books in a classroom or their presence in a library. I like to use the word banned because, sure, it’s more sensational, but mostly because it alliterates so nicely. As in . . .

No, we are not reading Fifty Shades of Grey by E. L. James, not only because the content is inappropriate for young readers, but because it isn’t very good.

That’s the interesting thing, most of the books on the banned or challenged book list are the same books that have been taught in schools for decades. In other words, most of the banned books are the best books.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”Most of the banned books are the best books. #BannedBooks #BookBurning #Censorship #GreatBooks” quote=”Most of the banned books are the best books.”]

There’s a reason for this: the best books are often provocative.

Books that aren’t banned ask little of readers. They affirm our values and fulfill in the end what they promise in the beginning. Books that aren’t banned, are often bland books.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”What should we read in school, bland books or banned books? #BannedBooks #GreatBooks” quote=”What should we read in school, bland books or banned books?”]

Books that make demands of its readers are challenged. Books that challenge readers to look at the world differently are burned. Books that startle and shock us out of our comfort zone are banned. These are the books we should be reading.

The books that do this, are the best books, and they are the banned books.

Here’s a list of some books that have been challenged; it’s also my recommended reading list. Its a list of books that everyone should read before they die, or better yet, long before they die so that having read them may do some good.

These next three I actually haven’t read, but I’ve read what my students have written about them. These stories had an impact. Students understood, in a meaningful way, something more about our indigenous neigbours, systemic racism, and the girl with no hope.

Image: HBO

Kevin De Young stated recently that he didn’t understand Christians watching Game of Thrones. From the comments following his post, it’s obvious that this is a bit of a contentious issue. I don’t think that Kevin De Young is necessarily wrong, but I do think that there is one reason why some Christians might watch Game of Thrones.

Before I engage his main idea, I have a few preliminary, knee-jerk reactions to his post:

First: A particular strain of North American Christian is particularly sensitive to sexual content. DeYoung’s post only questions this. Ten of John Piper’s explanations of the Twelve Questions to ask before You Watch Game of Thrones are centered on sex. That violence in Game of Thrones doesn’t seem to be a concern suggests an imbalance.

Second: Because he has not seen Game of Thrones (“Not an episode. Not a scene. I hardly know anything about the show.”) I don’t think De Young is qualified to publically comment on the show. The question a discerning Christian viewer must ask about questionable content (coarse language, violence, and nudity) is not whether or not it is present, but whether or not is it gratuitous. I have no problem with anyone choosing to avoid a program because of the content, but this does disqualify them from making a public critique of the show. I have had many frustrating conversations with people bent on banning books they’ve never read–Of Mice and Men, The Great Gatsby and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe were the subjects of three of these conversations.

Third: I find his use of the adjective “conservative” to be puzzling. De Young is baffled that many “conservative Christians” are watching the show. Why not just “Christians”? With this usage, he seems to be suggesting that there are all sorts of things we might expect from _____________ Christians, but conservative Christians should know better. There is so much damage done in the church through the deliberate perpetuation of divisions within the body of Christ, and they are often completely imaginary.

Fourth: De Young’s post is short because “the issue doesn’t seem all that complicated.” Oversimplification is a dangerous thing. I concede that over-complicating simple issues is also a danger–which is this? I don’t think too many things are simple. In this post, De Young is oversimplifying a complex topic: the Christian engagement with culture.

[tweetshareinline tweet=”OK, so why might some Christians watch Game of Thrones?” username=”Dryb0nz”]

Game of Thrones is art. It may be bad art or art to be avoided, but it is art. It is a product of our culture and it contributes to the discussion about what it means to be human. Christians have some important things to say on this topic, and should not exclude themselves from the table. Most Christians should be paying attention to this conversation, and some Christians might need to pay attention to the contribution that Game of Thrones makes to this conversation. The stakes are high, and, like I said, we have some important things to say on this topic.

[tweetshare tweet=”Some Christians ought to be paying attention to the contribution that Game of Thrones makes to the conversation: What does it mean to be human?” username=”Dryb0nz”]I’ve recently read a book called, How to Survive the Apocalypse by Robert Joustra and Alissa Wilkinson. In Chapter 7 — “Winter is Coming: The Slide to Subjectivism,” the authors suggest that Game of Thrones “gives us a picture of the world that could (and can) be but not the world that is.” Of course, the dragons and whight walkers are fantastic, but Joustra and Wilkinson are talking about one of our cultural pathologies that is on display in Game of Thrones–instrumentalism. Less and less, in Western culture, do we make decisions based on morals, ideals or principles. We weigh costs and benefits, and these are measured on a scale of personal fulfillment. Whatever benefits me is meaningful; I get to decide what benefits me–meaning is subjective.

The problem is that we live in a world that has a bunch of other people living in it too, and these folks present conflicting meanings. Very quickly we are faced with a problem: How do we decide whose meaning is more meaningful? The answer is simple: whosoever is the stronger. Consequently, everyone wants power, for only with power can my idea of personal fulfillment be realized for me. This is, perhaps, the reality to which we are headed. This is the world of Game of Thrones–“You win, or you die.” Because Game of Thrones gives us a peek at our possible future, it can be taken as a warning. We aren’t supposed to find the sex and violence stimulating, we are supposed to find it offensive because they are being used as tools to achieve a particular idea of personal fulfillment–this is something hellish.

If the show uses sex and violence simply to titillate and entertain, it is gratuitous sex and violence, and Christians ought to avoid this show. If the show condemns the instrumental use of sex and violence, then we are on the same page as the creators and watching the show will enable us to engage in meaningful dialogue with our culture, so that we might yet pull back from the slide to subjectivism. The problem is, I suspect the show uses the sex and violence both gratuitously and as a signifier of important ideas. See what I mean? It’s not simple.

One of the problems with the sex in Game of Thrones is that it distracts Christians from much more important and much more dangerous ideas than the sex and nudity. It would seem that the artists who create Game of Thrones are concerned about the increased role that power is or might be, playing in our culture. As Christians, we are concerned about that as well and we might, perhaps, be thankful that they pointed it out in such a way that so many people are paying attention. Christians have something far more to contribute to the conversations about Game of Thrones that go way past nudity–in the Gospel, we have the resources to challenge subjectivism, instrumentalism, and power before they transform our culture into one that too closely resembles what we see in the television program. Some Christians will need to be watching the show in order to take part in this important conversation.

[tweetshare tweet=”Sex in television is a problem because it distracts Christians from ideas that are much more dangerous than nudity. ” username=”Dryb0nz”]

Am I arguing that all Christians ought to watch Game of Thrones? Certainly not. Many should stay far from it because of the sex and the violence–it will cause them to sin, or another to stumble. Others should stay away from it because no Christian should ever passively consume a show like Game of Thrones, or any show for that matter. We are not of the world, but we are in it, and if we are going to be in it, some of us will need to understand it–this takes a lot more work than many people want to do, so these, too, should avoid shows like Game of Thrones.

When it comes to our interaction with culture, Christians often find themselves caught between a desire to be innocent as doves and to be as wise as serpents. It seems that it is Christ’s desire that we be both. So we, with the power of the Holy Spirit, are left to sort it out. This conversation has been going on for a long time; DeYoung leaning more toward a Puritan position, and my ideas coming out of a more Kyperean-Calvinist model.

Whatever position we take in this conversation, I believe these things are important:

What do you think? Is there a place for some Christians to watch Game of Thrones?

Image: HBO

Ahmadreza89 / Pixabay

Some people refer to Easter as “Zombie Jesus Day.” I’m guessing they are being provocative or trying to impress their like-minded friends. Perhaps it is because of this attitude that Christian writer Eric Metaxas has taken the position that zombies are a parody of the resurrection of the dead. I think zombies are much more than a parody, and they can be part of a gospel conversation with our children and even with our unchurched neighbours.

Jesus died and, after that, he walked around. These are two of the main things that zombies do, and it is upon these two qualities that the case for zombie Jesus is based. Missing, of course, is the third main characteristic of the ambulatory dead: the mindless consumption of living human flesh.

Zombies turned up in popular culture about a century ago, but they really took off with George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) and they’ve been going strong ever since. Why this popularity? The simple answer is that there is something about the zombie horde that resonates with our culture. Given the popularity of zombie narratives, it must be resonating a lot and has done so for almost fifty years. Why?

The popularity of zombies is due to the popular belief in our culture that we have outgrown Christianity and that materialism is probably true. By materialism I mean the belief that reality is material, and only material. There’s no room for the spiritual – no such thing as God or the human soul.

More and more we have organized our lives and our society around materialism. On a popular level, we don’t really dig too deeply into the implications of materialism on human identity and the meaning of life. In general, we don’t have time to read and think about these heady issues.

But we do have time to go to the movies. Many movies reinforce a materialist philosophy, but some question it. Zombie movies are among these. The zombie is a monster and, like all monsters, it is trying to tell us something about ourselves, something that we are trying to suppress. Zombies are an embodiment of our fears of a possible future if materialism is true.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”The zombie is a monster and, like all monsters, it is trying to tell us something about ourselves, something that we are trying to suppress. Zombies are an embodiment of our fears of a possible future if materialism is true. #ZombieJesusDay #Zombies” quote=”The zombie is a monster and, like all monsters, it is trying to tell us something about ourselves, something that we are trying to suppress. Zombies are an embodiment of our fears of a possible future if materialism is true.”]

We are human beings, so we have first-hand experience with what one is. We know how human beings respond to a beautiful waterfall. We know what it means to fall in love and we know what it means to be very, very sad. We not only think thoughts, but we can think about our thoughts. Is any of this possible if materialism is true? Even in a secular society, there is enough in this question to cause some doubt. Monsters turn up when we have doubts, and they keep coming back until they are dealt with. With the popularity of the zombie, we know that there are some doubts about being human in a materialist context. If there is no spiritual dimension to reality, would we respond to beauty as we do? Have emotions like love? Could consciousness signify that a human is more than matter? If materialism were true, wouldn’t we be zombies? Are we zombies?

The Apostle Paul’s faced some resistance to the resurrection of the dead as he proclaimed it. The ancient Greek culture, too, had some incorrect ideas of what a human being was. Gnostics and Platonists taught that the body was evil, or at least inferior to the spirit. The resurrection of the body didn’t make any sense to them. Why would we want to resurrect that old thing? We can see very well what happens to the body after the spirit has left it—it rots and wastes away. If humanity were to live beyond death, it would be in spirit, the good part, not in the body. Paul’s response to this incorrect anthropology is found in 1 Corinthians 15:35-44. Paul writes of a someone who seems to be stating that the resurrection of a corruption like a rotting corpse is impossible. Perhaps this “someone” imagined a shambling horde of animated, partially decomposed corpses. Paul declares this talk foolish and explains that as a dead seed goes into the ground and comes out completely new, so too, the “perishable” body goes into the ground and is resurrected “imperishable.”

[tweetshare tweet=”Paul argues against zombies in 1 Corinthians 15:35-44. ” username=”Dryb0nz”]The error of Paul’s audience reduced the essence of humankind to spirit, where modern materialism reduces man to mere body. Paul says that you will get the resurrection all wrong if you fail to understand that a human being is both body and spirit and that the resurrection will be of the whole person.

The error of Paul’s audience reduced the essence of humankind to spirit, where modern materialism reduces man to mere body. Paul says that you will get the resurrection all wrong if you fail to understand that a human being is both body and spirit and that the resurrection will be of the whole person.

When Jesus rose from the dead he had a new, resurrected body. This is what Paul’s audience needed to understand about the resurrection. Paul’s words to the church in Corinth apply to our culture as well. We need to understand that Jesus wasn’t just reanimated body, but a heart and mind and spirit as well. Consequently, he was nothing like a zombie. And rather than eating living human beings, Jesus was satisfied with eating fish with his friends (Luke 24:42-43). This is very unzombie-like behavior.

It is clear that in AMC’s The Walking Dead TV series, one would rather be truly dead than one of the “walkers.” A materialist resurrection is much worse than the nothingness of a materialist death. Disrespectful internet trolls aside, I don’t believe that the zombie apocalypse is a parody of the resurrection of the dead; I believe it is a lament that resurrection isn’t what it used to be before we grew out of our belief.

The gospel message to the zombie culture is that human beings haven’t changed. We have always been a lot more than our material bodies and we still are. Our need for salvation has also not changed – there are no true zombie movies that don’t clearly present the truth of human depravity. The good news is that the God who made us with not just a body, but a heart and a soul and a mind as well, loves us so much that he redeems all of me. Jesus wasn’t a zombie, and neither am I. This is the comprehensive resurrection we celebrate this Easter.

A version of this article was first published for The Christian Courier at christiancourier.com.

Last week my school received a visit from the Honourable Judith Guichon, the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. The lieutenant governor the representative of Queen Elizabeth II in BC. The visit followed the expected protocols–teachers dressed formally; Her Honour was accompanied by an Aide-de-Camp in full RCMP dress uniform; she entered the assembly in a processional and various other formalities were followed; we sang the national anthem and “God Save the Queen.”

Last week my school received a visit from the Honourable Judith Guichon, the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. The lieutenant governor the representative of Queen Elizabeth II in BC. The visit followed the expected protocols–teachers dressed formally; Her Honour was accompanied by an Aide-de-Camp in full RCMP dress uniform; she entered the assembly in a processional and various other formalities were followed; we sang the national anthem and “God Save the Queen.”

Some Canadians love all things royal. They’ve got a picture book on their coffee table and commemorative plates on their walls. Others like the idea of Canada’s relationship with the English monarchy. It’s part of our history and what makes us unique–it gives us a little class, and how can you not admire the depictions of Elizabeth II on Netflix’s, The Crown. But some people think the whole business is a royal waste.

I have concluded that Christians ought to celebrate the monarchy.

The Royal Family has an important role. Never mind the good that they do through the Royal visits and causes they for which they advocate. Even if you take all these significant contributions off the table, they play a significant role by just being royal.

One of the reasons some might question the value of royalty, indeed the whole English aristocracy, is because we believe in equality. We have come to accept equality as a foundational truth and a desired end. It follows that democracy is the best sort of government, and aristocracy and democracy don’t go together.

But we would do well to remember Winston Churchill’s quip that “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” Democracy doesn’t work very well because it needs a citizenry that is good and wise, and people are usually neither. The reason democracy is better than all other forms of government is because it takes the fact of human depravity and decentralizes it.

In a 1943 essay titled “Equality,” C. S. Lewis explains how the value of equality and democracy is grounded not in Creation, but in the Fall.

I do not think that equality is one of those things (like wisdom or happiness) which are good simply in themselves and for their own sakes. I think it is in the same class as medicine, which is good because we are ill, or clothes which are good because we are no longer innocent.

According to Lewis, equality is a necessity to mitigate the power of evil in a fallen world. Equality came after the Fall to counter the desires of evil men to oppress and exploit each other.

Lewis from “Equality”:

[T]he function of equality is purely protective. It is medicine, not food. By treating human persons (in judicious defiance of observed facts) as if they were all the same kind of thing [like widgets], we avoid innumerable evils. But it is not on this we were meant to live. It is idle to say that men are of equal value. If value is taken in a worldly sense – if we mean that all men are equally useful or beautiful or good or entertaining – then it is nonsense. If it means that all are of equal value as immortal souls, then I think it conceals a dangerous error. The infinite value of each human soul is not a Christian doctrine. God did not die for man because of some value He perceived in him. The value of each human soul considered simply in itself, out of relation to God, is zero. As St. Paul writes, to have died for valuable men would not have been divine but merely heroic; but God died for sinners. He loved us not because we were lovable, but because He is love. It may be that He loves all equally – He certainly loved us all to death. . . . If there is equality, it is in His love, not us.

In Western cultures we accept as normative the virtues of equality and of democracy. The “you are no better than I am” sentiment results in a reluctance to submit to legitimate authorities–the boss, the coach, the government, our parents. This sort of thing seeps into the Western Church as well. There is a hesitance to submit to the church leadership. Some denominations are made up of autonomous congregations. Some congregations don’t even have a denominational affiliation. These conditions lean away from God’s creational design.

As Canadians, we have a connection to the Royals that the Americans do not. Americans have their Declaration of Independence which tells them that all men are created equal. It just ain’t so. As Canadians we have an advantage over our American brothers and sisters in that we have in the Monarchy a powerful symbol to remind us who we really are–and I don’t mean, former British subjects.

The benefit of the Royal Family and the aristocratic class is that they ground us in reality. They are not just a symbol of a faded empire, but of a Creational truth that we are not, in fact, created equal. They remind us of the Biblical truth that our value is not is our “equal value as immortal souls,” but in Christ’s love for us. There is some value in our “inequality,” in our uniqueness, as we serve as different (unequal) parts of The Body (Romans 12).

[tweetshare tweet=”The benefit of the Royal Family is that they ground us in reality. They are not just a symbol of a faded empire, but of a Creational truth that we are not, in fact, created equal. ” username=”Dryb0nz”]Perhaps the main reason why people argue that the Royals are irrelevant is out of a misplaced allegiance to equality. Perhaps not, but as we watch Downton Abbey or The Crown or the various visits, appearances and events featuring the Royals, it might be a beneficial, even spiritual, discipline to reflect on what all the pomp and circumstance might signify, and how it might bring us toward the truth of who we are in the Kingdom.

[tweetshare tweet=”Perhaps people argue that the Royals are irrelevant is out of a misplaced allegiance to equality. ” username=”dryb0nz”]

geralt / Pixabay

What can you spend, save and waste?

I asked my students this question and the answer is about 50/50–money and time.

You’d expect people to say money because that’s the right answer. In what way is time anything like money?

They are not alike at all, but we use exactly the same verbs to describe what we do with them. You don’t spin a banana, or peal a yarn. You don’t run with petunias and plant scissors. Yet somehow we’ve managed to manage time as if it were something like money.

Richard Lewis explains in “How Different Cultures Understand Time“:

For an American, time is truly money. In a profit-oriented society, time is a precious, even scarce, commodity. It flows fast, like a mountain river in the spring, and if you want to benefit from its passing, you have to move fast with it. Americans are people of action; they cannot bear to be idle.

This view of time is by no means universal. At a social gathering a few years ago, a Cameroonian man said to my wife , “You people . . . ” (By this he, of course, meant you Americans.) “You people have such a strange way of thinking about time. You think of it as something you can grasp, something you can hold in your hand.”

For North Americans and most northern Europeans, time is linear. It’s a line, a time line, with evenly spaced hash marks designating the minutes and hours, days and years. This line extends into both the past and the future and in the middle is a point called the present. The line of time continuously slides at a constant speed through the present from right to left. On the future side of the present we affix plans and promises–commitments to others and to ourselves as to what we will do by particular points on the time line. In our culture, we focus a lot on the future–in both hope and fear.

I can’t pretend to know anything firsthand about what is called “Africa time,” but one of the pastors at my church was born and raised in Kenya. He tells me that in Africa people aren’t governed by the clock, rather they take the view that “things will happen when they happen.”

Here, if I arrange to call a friend at 3:00–I call him at 3:00. In Africa, my friend says, “I would be crazy to expect the call at 3:00, because 3:00 really means ‘sometime in the afternoon,'” and it is not a surprise if the call didn’t come in at all. That’s OK, because “tomorrow is another day.”

Why this seeming irresponsibility in keeping appointments and living up to agreements?

It’s all about relationships.

In African culture almost everything is about relationships. My pastor explained, “If I were on my way somewhere and I encountered my friend Trent, I would stop and have a conversation.” A present conversation is too important to cut off before it’s naturally concluded–until then, there is no other place to be.

African time bends and stretches according to the present relational needs. It matters not what a clock might say. Africa is a big continent and it’s got many different cultural groups, so generalizations are dangerous, but there is apparently some commonality in how time is conceived–and not only in Africa, but in Latin America as well.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”In our culture we consider an event to be a component of time whereas other cultures often consider time to be a component of the event. #time #LinearTime #TimeasCommodity #LatinTime #AfricanTime #WasteofTime #Boredom” quote=”In our culture we consider an event to be a component of time whereas other cultures often consider time to be a component of the event.”]

Interestingly, in our culture, we suffer from boredom if we have too much time. We suffer stress if we have too little.

I asked my friend if, in the absence of mechanical time, Africans experience boredom and stress. He said that an African person will be bored if they are alone, and experience stress when there is a brokenness in their community. Again, it comes down to the primacy of relationships.

I’m not sure if the African conception of time is morally superior to mechanical time, but I think, with its focus on relationships, that it might be. But we have to admit that there are also many advantages to our Western notion of time; I love the timeliness by which German trains operate.

When it comes to conceptions of time, whether Christian or not, residents of Northern Europe and North America have a “secular” view of time. We should, therefore, be hesitant to claim that we have a “Christian” or a “Biblical” worldview–because in our understanding of time, we do not. We have a pretty “secular” worldview.

skeeze / Pixabay

I recently heard a pastor refer to France as a spiritual wasteland, and this wasn’t the first time I had heard this.

Twenty-one of our students went to France this past spring break and I asked them if they found this to be true. They agreed that French culture is very secular. Very few people in France go to church, and they don’t really talk, or even think, about God. They have beautiful churches, but the students observed large gift shops in two of the most beautiful churches they visited, Notre Dame and Sacre Coeur.

But, they also saw evidence that perhaps the French aren’t as spiritually dry as we might think, and that they are, in some ways, expressing some aspects of honouring the Creator better than we do.

The most obvious example for the students was the French approach to food. The French value food, so when they eat, they take their time. A meal is not a mere biological necessity between work and an evening Bible study. The meal is one of the most important events of the day. The students said, “Even their fast food is slow.”

And meals aren’t just about the food. They are very much about the conversation that takes place over the meal. The French enjoy nothing more than great food with good friends. Here, restaurants try to maximize the number of seatings in an evening by carefully moving diners from the appetizer to the bill as quickly as possible without them feeling rushed. In France, you and your friends are expected to enjoy each other’s company for hours. If you want a bill, you have to ask for it. If you have a table, you have it for the night.

Rather than serving groceries in the same store that also sells underwear and motor oil, the French have rows of small, independently owned specialty stores. Each only sells one thing–cheese, meat, pastry, bread, fish, vegetables. The idea is that if you specialize, you can better ensure the quality of your wares, and the resultant meals will be a lot more enjoyable.

The French don’t believe in God, hence the appellation “godless,” but they treat many of his gifts with the utmost respect. They take the good gifts of God and treat them as the treasures they are.

Our culture conceived of Kraft Dinner which sells for $1.27 a box and takes less than 10 minutes to make and even less to consume even if we include the time it takes to offer a prayer acknowledging God’s gustatory providence.

I will not choose which approach is better, to love the gift but ignore the giver, or to love the giver, but disparage the gift. It seems to me that loving both would be the ideal.

This post was previously published at http://insideout.abbotsfordchristian.com/

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑