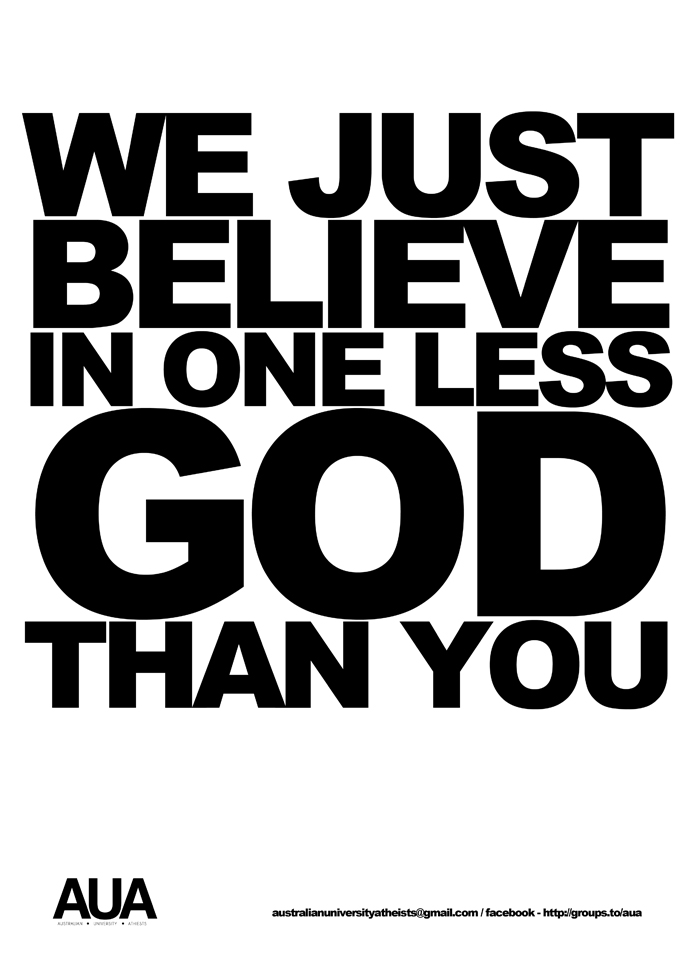

A common argument against belief in God–does it stand up?

Actually, that’s not all there is to it.

I mean, it’s not quite so simple.

Affirmed atheist, Ricky Gervais used this argument when he was a guest on Stephen Colbert. The YouTube clip has received over 4 million views.

In the interview he said that there are about 3000 deities that people have worshiped at one time or another and Christians don’t believe in 2,999 of them, the atheist simply goes one god further. Gervais’ exact words are:

I don’t believe in just one more.

Colbert didn’t respond–perhaps he was just being polite, but what is the Christian response to Gervais’ argument?

[click_to_tweet tweet=”*I just believe in one god less than you.* What I would have said to Ricky Gervais if I were Stephen Colbert. #atheism #RickyGervais #StephenColbert” quote=””I just believe in one god less than you” (sic). What I would have said to Ricky Gervais if I were Stephen Colbert.”]

“I don’t believe in just one more”

This argument needs to be unpacked a little.

Gervais is suggesting that there is a logical, and therefore necessary, step that Christians (and other monotheists) fail to make. His use of the term “just” suggests that this step is insignificant. This is far from the case–the step is neither a logically necessary nor is it insignificant.

His argument is that the rejection of the final god is the same as, and in line with, the rejection of all preceding gods. But this is wrong. It does not follow that if one rejects 1 god, one must reject the remaining 2999. Nor does it follow that if you reject 2999, you must logically reject the last.

This step, the one that Gervaise takes, has only been taken by very few, and these only recently. Of all the millions of people that ever lived in all of the remote corners of the world, all of them have come to the same conclusion. They concluded that there is more.

Belief in any one of the 3000 gods is an acknowledgment of some form of transcendence–that there is something beyond or above the range of ordinary or merely physical human experience. The belief in any deity is a claim that there is some external standard to which we must all align our lives.

The Atheists leap of faith

Rather than making a small step in line with the rejection of the first 2,999 gods, Gervais is making a giant leap in the opposite direction. He doesn’t go one itty-bitty step beyond Christianity, as his “just” implies. He, and those like him, are breaking with conclusions arrived at by the rest of humanity. These conclusions have been arrived at independently, over thousands of years on human history.

That all of humanity has arrived at the same conclusion, isn’t irrefutable proof that their conclusion is true. People who believe in God certainly take a leap of faith.

Gervais points this out as he explains atheism in a nutshell:

You say, “There is a God.”

I say, “Can you prove that.”

You say, “No.”

I say, “I don’t believe you then.”

Perhaps many in Colbert’s audience feel that Gervais has scored a point against believers, but he hasn’t. A theist can illustrate the atheist leap of faith similarly:

You say, “There no spiritual reality beyond the material.”

I say, “Can you prove that.”

You say, “No.”

I say, “I don’t believe you then.”

I think Gervais would acknowledge his leap of faith.

The question is–Who takes the greater leap? The person who says that everything that we see in the cosmos and through our experiences in life is the result of material processes or the person that says there is something more than matter and its movements and modifications.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”Who takes the greater leap of faith, the theist or the atheist? #atheism #RickyGervais #StephenColbert” quote=”Who takes the greater leap of faith, the theist or the atheist?”]

The conversation can start here, not where Gervais thinks he ended it in the Stephen Colbert interview.

Last week my school received a visit from the Honourable Judith Guichon, the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. The

Last week my school received a visit from the Honourable Judith Guichon, the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. The

In his article called “

In his article called “ Most people think Twitter began in 2006, but a form of it existed in my grade 7 classroom long before that. I didn’t call it Twitter, I called it “Notion Notes.”

Most people think Twitter began in 2006, but a form of it existed in my grade 7 classroom long before that. I didn’t call it Twitter, I called it “Notion Notes.”